Theory of attacks and cryptanalysis #

The Ultima Thule of encryption #

The one-time pad (OTP) encryption was first described by Frank Miller in 1882. In 1917 it was re-invented, and on July 22, 1919, U.S. Patent 1,310,719 was issued to Gilbert S. Vernam for the XOR operation used for one-time pad encryption.

The OTP encryption technique is the most secure and cannot be cracked—if used correctly. It requires a one-time pre-shared key of the same size (or longer) as the message being sent.

If a key is:

- truly random;

- at least as long as the plaintext;

- never reused partly or as a whole;

- kept completely secret;

then it will be impossible to decrypt or break the resulting ciphertext. This claim is backed by a rigorous mathematical proof.

However, this theoretically ideal system has some unresolved practical problems in real life:

- How to transmit the key to the decrypting party safely?

- How to keep both of the keys secure?

- How to generate so many totally random keys for each large-sized message?

- How to provide message authentication, the lack of which can pose a security threat in real-world systems?

The impossibility of resolving these problems on the one hand, and the requirements towards the ease of use, on the other hand, have caused the transition from theoretically secure systems to practically and/or computationally secure ones.

This means that we (prove and) declare a system to be secure if it cannot be cracked in the foreseeable future—that’s a practically secure system.

Or if we prove that “if you can break my cipher, you can solve this hard problem”, meaning that our problem is at least as difficult to solve as some other problem. So if the problem is indeed hard to solve, cracking our encryption must require at least as hard computations to be performed.

The above-mentioned transition conditioned the arrival of different models of attacks on modern cryptosystems. Examples of the most relevant of these attack models are provided below.

Theoretical attack models #

Ciphertext-only attack (COA) – the adversary only has access to a limited number of ciphertexts. The adversary doesn’t have access to the encryption key.

Example: Eve steals a random bunch of ciphertexts from Alice’s purse, but has no idea what they mean.

Known-plaintext attack (KPA) – the adversary has access to a limited number of plaintext/ciphertext pairs. The adversary doesn’t have access to the encryption key.

Example: Eve overhears an encrypted communication between Bob and Alice, and later sees them meet at Fulton Street. Eve can now guess that the communication contained the words “Fulton Street” somewhere, a form of known plaintext attack.

Chosen-plaintext attack (CPA) – the adversary is able to freely choose an arbitrary plaintext and get the encrypted ciphertext. The adversary doesn’t have access to the encryption key.

Example: A poorly designed file storage system uses the same key to encrypt everyone’s files. It also lets anyone see anyone’s files (in encrypted form). For example, Eve knows that Bob uses a certain service. Eve also registers within the service and starts encrypting arbitrary files (which she can choose) and looks at the resulting ciphertext. This allows Eve to recover the service’s encryption key and decrypt Bob’s data.

Chosen-ciphertext attack (CCA) – the adversary is able to freely choose arbitrary ciphertext and receive the matching decrypted plaintext. The adversary doesn’t have access to the encryption key.

Example: Eve breaks into Bob’s house while he is sleeping and replaces the ciphertext he was going to send to Alice tomorrow with a new one of her choosing. She then eavesdrops on their communications (encrypted or not) the next day to try and work out what Alice read when she decrypted the fake ciphertext. (Variants of this involve Eve not just creating a new ciphertext, but slightly modifying the existing one.)

Open key model attack (OKMA) – the adversary has some knowledge about the encryption key (that can range from some key bits to full freedom of knowing or even choosing the key). Examples: related-key attack, known-key distinguishing attack, chosen-key distinguishing attack. The adversary doesn’t have access to the encryption key.

Example (related-key attack): Bob uses his WEP-enabled wireless Internet connection. Eve analyses Bob’s connection and tries to decrypt his encrypted packets—unlimited amount of which is available to Eve. WEP protocol uses RC4 cipher with 24-bits initialization vector (IV) in each packet. RC4 encryption key is the IV concatenated with WEP long-term key. This key has been chosen by Bob manually (derived from the password) and remains unchanged. Because of the birthday paradox, for every 4096 packets, two of them will share the same IV and, consequently, the same RC4 key. Knowing that, Eve intercepts the necessary amount of Bob’s packets and receives an opportunity to attack them.

Techniques of cryptanalysis #

-

Side-channel attack (SCA) – the adversary tries to access the information about the encryption key with a help of intelligence methods. This typically includes observation of physical implementation of a cryptosystem: analysing the timing information, power consumption, electromagnetic leaks, system faults, recovering wiped data from storages, etc.

-

Social engineering – the adversary uses psychological manipulation to trick the victim into performing actions or divulging confidential information.

-

Purchase-key attack – adversary uses bribery to obtain secret keys or other sensitive information.

-

Rubber-hose cryptanalysis – adversary uses torture or coercion to extract some cryptographic secret from a person (a key, a password, etc.)

Categorisation of concrete attacks on cryptosystems is typically based on the action performed by adversary, meaning an attack can be active or passive.

Active and passive attacks #

An active attack attempts to alter the system resources or affect their operation: e.g., modify the information, initiate unauthorised transmission of information, perform unauthorised deletion of data, deny the access to information to legitimate users, etc.

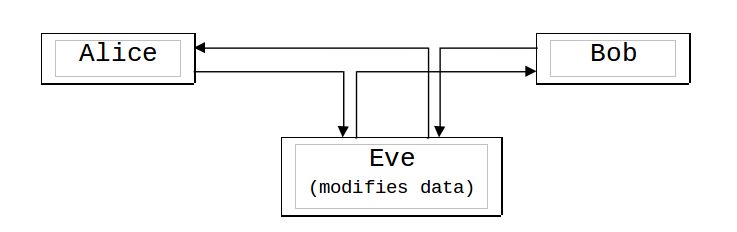

A typical scheme of an active attack looks like this:

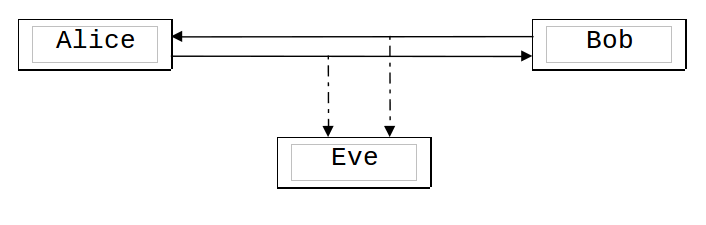

(Alice and Bob are the legitimate communication entities, Eve is the attacker.)

A passive attack attempts to learn or use the information from the system but doesn’t affect the system resources: e.g., intercepting and eavesdropping on the communication channel.

A typical scheme of a passive attack looks like this:

Examples of attacks #

Well-known active attacks:

-

Man-in-the-Middle (MitM): man-in-the-browser, meet-in-the-middle, miss-in-the-middle, replay attacks, TCP hijacking, LogJam, FREAK, etc.

-

Denial-of-Service (DoS): SYN flood, ping-of-death, Smurf attack, LAND attack, etc.

-

Spoofing ARP/DNS responses, IP/MAC-addresses, Referer headers; faking CallerID, email, GPS data; poisoning of file-sharing networks, etc.

Examples of passive attacks:

- Webtapping

- Network scanning (port or idle scanning)

- Network traffic sniffing

Cryptosystem vulnerabilities #

Since a cryptosystem is a component of the common computer system/technology, there are some additional security issues that require attention, such as vulnerabilities.

Correct usage of strong cryptography does guarantee protection against all known theoretical attacks. However, it does not guarantee a high level of complex computer system security protection against all possible threats.

We recommend taking some time to educate yourself about cryptographic vulnerabilities. You can start with these external resources: